Hello! I’ve been sharing quite a few cinemagraph posts on social media and today I’m excited to share a quick step-by-step on how I put them together in Photoshop. I’m sure there are several methods and programs people use to create these moving images, but honestly, Photoshop, I can’t afford your “full suite” nonsense, so I have to learn how to do this on Photoshop. <3

The final product (above) is something very simple (for the sake of showing how this gets broken down).

Video Clips

My files begin as video clips - I’ve been shooting these on the little Fuji, which makes it easy to move around and do something quickly. If I shoot one longer video and try different positions, I can easily trim the video once it gets imported onto the computer. In fact, that’s an important step before even bringing it into Photoshop. That helps isolate the clip way more easily than trying to look at a full-length thumbnail.

Here I have multiple original video files open to decide which clip will be the base for the cinemagraph. I like to trim the clip to be somewhere between 10-30 seconds.

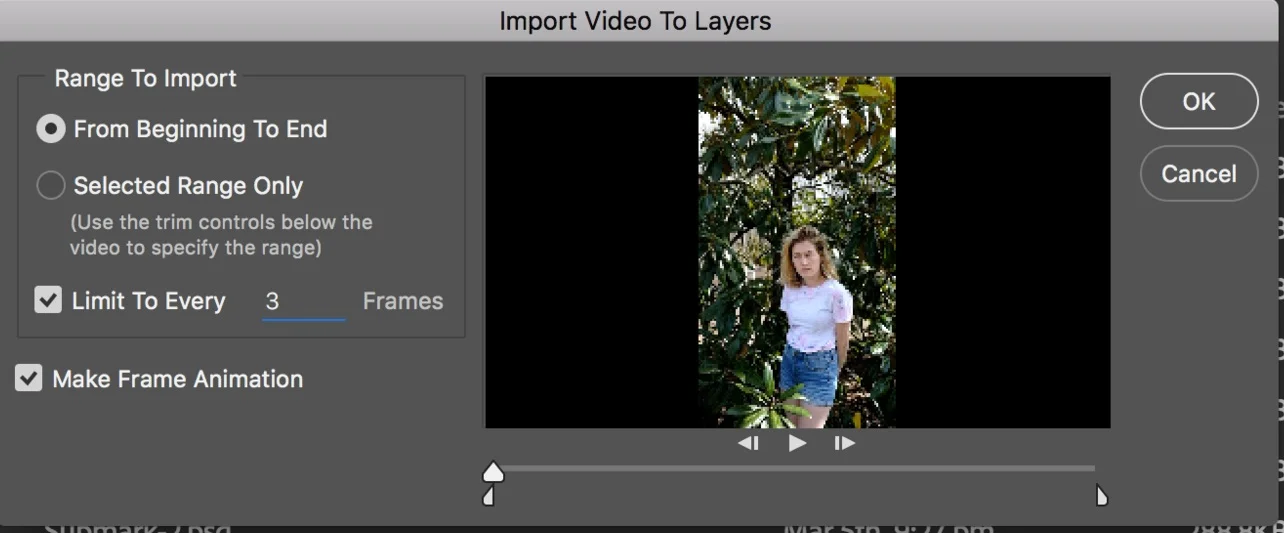

Once I’ve narrowed down which clip I’d like to use, I open Photoshop and go to File>Import>Video Frames to Layers. From there, I choose that saved video clip.

In the Import window, depending on how fine-tuned you’ve trimmed your video file, you can choose to use the full clip or select only a range of the clip. Another way to to cut out unnecessary bulk is to limit the amount of frames that get imported. I usually limit to every 2-3 frames, depending on the length of the clip.

Preparing the Frames

If you don’t already have the timeline window open at the bottom of your workspace, you can find it under Window>Timeline. I like to start off by selecting all of my frames and changing the duration to “No Delay” for the GIF format. There’s a little menu in the top-right hand corner of the timeline bar, and from there I can “Select All Frames.” I can then select the little duration at the bottom of one of the frames and adjust to “No Delay” or “0 seconds.” They should all update.

Now, to decide what my top layer will be. Because I’ve determined here that I want the subject (me) to be stationary, that will have to be the part that covers up the other shuffling layers. I like to go through and play the animation (you can hit the space bar to do this) and pick my favorite still. I then go to the layer that corresponds with my selected frame - you can scroll through the layers panel (right of my screen) to find the selected layer and hit the little duplicate icon or Command + J to make a copy. That copy then needs to move on top of all of the other layers. You can either physically click and drag it until it’s on top, or hit Command + Shift + ] .

Another important little tidbit here. Because we’re working with multiple layers/frames, we’re going to want this layer to be consistently in place over all of them. Make sure you select these three options for the top layer, because this locks in the opacity and position of this layer across all frames. You can do this with any additional normal or adjustment layer.

Masking

Once you add your top layer and select the locked opacity and position options, hit play. If your animation isn’t playing and you’re just looking at your top layer (while the frames are visibly changing in the Timeline panel) you’re actually doing it right. We’re going to make it do fun things next. Before I do anything else, I rename that top layer by clicking on the name and just calling it something that makes it stand out. Something wild like “top layer” does the trick. The next step involves a mask. I just hit that little rectangle/circle icon at the bottom of my layer - you can see my cursor hovering on it in the screenshot above. A little white rectangle should show up next to that top layer. This is good. If you look over to the lefthand tool panel, you may notice that your swatches are black and white at this point. This is also good.

The mask works by letting us erase or “un-erase” that top layer without actually affecting the original layer. We could do a lot of things on that mask, delete the mask, and the layer would be untouched. Rad, I know. The black and white act as adding/subtracting tools for the mask. White = the image, black = erased space. Because the majority of my frame here will be the moving leaves, I’ve decided to start with black and add in white for my body. I can simply go to paint bucket, make sure it’s filled with black, and “fill” the image. You won’t see any difference here, except that the rectangle next to the image will be black now. You can test this by playing the animation again, and you’ll notice that it doesn’t even look like you have a top layer anymore. This means it is doing the thing.

You can fine-tune the effect by playing the animation a little, adding some white in, playing it, adding some black, until everything looks the way you’d like.

Note the tiny white, Sasquatchian figure within the black rectangle. This is the mask at work.

Cropping

Totally optional but I wanted to mention it (as I did it here). Because video formats lend themselves to very long verticals, you may want to crop. You can do that with animations just as you would a normal image. Here I cropped to a 2:3 ratio (4x6). If you want Instagram-friendly dimensions, 4:5 is the ratio for you. Just click and drag until you’ve gotten the size you’d like. Bonus: If you want to be able to go back and tweak this crop, make sure the “Delete Cropped Pixels” option is unchecked. I like to leave this unchecked until I’m certain I like the crop, and then I delete the pixels to save space for exporting.

How to Loop

An aspect of cinemagraphs that can make them really effective is successful looping. I like to loop the motion in my cinemagraphs as often as I can. This varies in difficulty depending on the type of motion being captured.

In the case of the leaves here, it was a little tricky, but because they’re sort of randomly bobbling I can just cut the animation down frame by frame until the motion doesn’t jump. To try to ensure a smooth loop, I take my frames, duplicate them, and reverse the order. Then I go back into the areas where the two animations meet, and trim the redundant frames. To do this, I use the “Select All Frames” function from before. Now, I go to the little page icon at the bottom of the Timeline panel (see below).

At this point, only the new, duplicated frames should be selected. Then from that same right-hand menu, I select “Reverse Frames.” If you play your animation now, you should see a few awkward places where the animations butt up to on another. Here you can play with what frames to delete to make the motion meld together more smoothly. To keep the files small and the exporting easy, it’s good to shoot for ≤100 frames. Sometimes if I have to, I go up to 200, but that makes the files and exporting tough (especially if you’re working off of a laptop).

Export

Cinemagraphs can exist as GIF or video files, so depending on where you want to use them, you can do either. To export as a GIF, go to File>Export>Save for Web. As default, I like to keep my longest side <1000px, try to go for 256 colors and Diffusion dither to make it higher quality, and choose either Adaptive or Relative color scheme. Honestly, just play around here and learn what the different settings look like, and figure out what works for you. Size may be your limiting factor (for example, my file has to be <12MB for me to post in this blog, so I have to make sacrifices to swing that.

To export videos, go to that same File>Export window, and choose “Render Video.” I choose the option for iPads, iPhones, and mobile because that’s what I use videos for!

This has been very brief, but hopefully it’s given you some insight into my cinemagraph process or even helped you take the first steps to creating one yourself. Please leave a comment or shoot me an email if you think there should be more clarifying information, or if you found this helpful. Learning is the bee’s knees, so I want to facilitate that as best I can.

Thanks for virtually chillin’ - subscribe to the newsletter for updates about posts like these or extra special treats!